Rachel Armstrong

Rachel Armstrong is Professor of Experimental Architecture at the Department of Architecture, Planning and Landscape, Newcastle University. She is also a 2010 Senior TED Fellow who is establishing an alternative approach to sustainability that couples with the computational properties of the natural world to develop a 21st century production platform for the built environment, which she calls ‘living’ architecture.

Rachel Armstrong’s new book, Vibrant Architecture (Matter as CoDesigner of Living Structures), explores prospects for transformations of matter into habitable structures, which prompts a re-evaluation of how we think about sustainability – most particularly around coastal cities such as Venice.

Rachel has been frequently recognised as being a pioneer being added to the 2014 Citizens of the Next Century List, by Future-ish, is one of the 2013 ICON 50 and described as one of the ten people in the UK that may shape the UK’s recovery by Director Magazine in 2012.

In the same year she was nominated as one of the most inspiring top nine women by Chick Chip magazine and featured by BBC Focus Magazine’s in 2011 in ‘ideas that could change the world’.

ABSTRACT: Living images.

This presentation asks whether ephemeral traces that are produced at interfaces between liquid and air can actually shape material events.

At a time where we need to synthesise new, fertile relationships with the natural realm, the concept of “living” images is introduced. These are produced spontaneously by natural systems and inscribed in rich multi-layerd soil-like matrixes, as part of a “natural computing” process. Methods and instruments that may enable us to adopt an experimental approach to working with these transient, dynamic images are considered, which include the symbolic reading of traces in practices like scrying, to photography, algaeponics, dissipative structures, quantum biology and the material transformations of metabolic apparatuses. A range of experiments – such as Future Venice, Future Venice II, the Rauschenberg Residency Moon Writing project and Persephone – will be used to suggest how new toolsets may assist our exploration of what it means to be an image maker activating the liminal space between the ephemeral and material realms of the natural world.

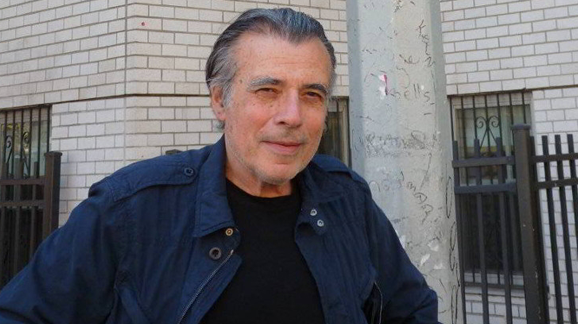

Arthur I. Miller

Arthur I. Miller is fascinated by the nature of creative thinking – in art on the one hand and science on the other. What are the similarities, what are the differences? He has published many critically acclaimed books, including Einstein, Picasso, Empire of the Stars and 137, and writes for the Guardian and The New York Times. An experienced broadcaster and lecturer, he has curated exhibitions on art/science and writes engagingly about complex social and intellectual dramas, weaving the personal with the scientific to produce thoroughly-researched works that read like novels. He is professor emeritus of history and philosophy of science at University College London.

His book Colliding Worlds: How Cutting-Edge Science is Redefining Contemporary Art (W.W. Norton) tells the story of how art, science and technology are fusing in the twenty-first century. To research it he interviewed leading figures in the world of contemporary science-influenced art and has spent time and lectured at CERN, the MIT Media Lab, Le Laboratoire, the School of Visual Arts and Ars Electronica. In 2013 he was a juror for the Prix Ars Electronica for Hybrid Art. See www.arthurimiller.com/ and www.collidingworlds.org/

ABSTRACT: Art, Science, Technology and the Scientific Image

Increases in abstraction, or dematerialisation, of the scientific image from the 15th century to the present reflects the struggles of scientists trying to visualise worlds beyond our senses. Although succeeding images were replaced, some never faded away. Rather they were clues for proceeding into ever-deeper domains of the micro- and macro-cosmos. I will discuss how this came about amidst intense, and sometimes personal struggles, concerning mathematics, philosophy, science and aesthetics. The 21st century brought further surprises for the image, and aesthetics as well, when art, science and technology fused and data visualisation became an art form.

Sean Cubitt

Sean Cubitt is Professor of Film and Television and co-Head of the Department of Media and Communications at Goldsmiths, University of London and Honorary Professorial Fellow at the University of Melbourne. His publications include Timeshift: On Video Culture, Videography: Video Media as Art and Culture, Digital Aesthetics, Simulation and Social Theory, The Cinema Effect, EcoMedia and The Practice of Light: A Genealogy of Visual Technologies from Prints to Pixels . Duke University Press will be publishing his next volume, Finite Media: Environmental Implications of Digital Technology. Among his co-edited collections are Rewind: British Video Art of the 1970s and 80s, Relive: Media Art History, Ecocinema: Theory and Practice, Ecomedia: Key Issues (Earthscan/Routledge 2015) and the open access anthology Digital Light (fibreculture 2015). He is the series editor for Leonardo Books at MIT Press. His current research is on political aesthetics, media technologies, environmental impacts of digital media and on media arts and their history. http://seancubitt.blogspot.co.uk/

http://goldsmiths.academia.edu/SeanCubitt

ABSTRACT: Untimely Ripped

Flusser traces the origin of writing to the succession of images, a succession in which the magical properties of the image as an instrument of action are broken down in the dependence of each image on its predecessors and successors for its significance. Writing is the order imposed on this mutual dependence. Photography in some way restores the magical: even today we have justified fears of being identified by but also with our image. Unlike a drawn, painted or etched picture, making a photograph is potentially instantaneous and therefore traumatic. Even if laboriously set up and composed, a photograph rips a moment out of the flux of time. The truth it claims as record comes at the price of no longer sharing the common fate of change. In this sense a still image is true to the extent that it is without meaning (a truth about the world, not about its significance for us). Moving images come from an intuitive attempt to heal the trauma and restore significance by supplementing each image with another, even faster than the production of still images. That the attempt was fruitless is obvious from the fact that we are still making movie after movie and still haven’t secured the significance of the world. The granular scan of digital cameras can be understood as an attempt to rewrite this problematic for an era in which machine-to-machine communication is at least as significant as human-to-human. This talk will explore these hypotheses.